Fossil Fuel Risk Bond Programs - Implementation Guidance for Local Government

John Talberth, Richard Mietz and Daphne Wysham • May 8, 2023

A policy innovation makes headway in the Pacific Northwest

WHAT ARE FOSSIL FUEL RISK BOND PROGRAMS?

In 2016 Center for Sustainable Economy proposed a commonsense solution for addressing the market failures associated with construction and operation of fossil fuel infrastructure – fossil fuel risk bond (FFRB) programs. Climate change is one, a market failure of breathtaking proportions. Add to that market failures associated with fossil fuel infrastructure itself – the vast network of coal mines, oil and gas wells, pipelines, refineries, oil trains, LNG trains and fossil fuel export terminals causing expensive physical and economic damages to land, air, water and frontline communities on an almost daily basis.

The International Renewable Energy Agency reports that air pollution and climate change caused by fossil fuel consumption generates externalized damages of $2.2 – $5.9 trillion each year. [1] By 2100 the White House, citing figures from Network for Greening the Financial System, predicts a hit in the order of 3 – 10% of GDP each year in the US alone. Fossil fuel risk bond programs are tools that regulators can use to begin to address these staggering externalized costs. They consist of two primary approaches:

- Suites of financial assurance mechanisms such as surety or performance bonds, trust accounts, letters of credit or catastrophic insurance that make fossil fuel infrastructure owners fully responsible for the financial and economic costs associated with explosions, spills, toxic air emissions, abandoned infrastructure and other discrete risks associated with fossil fuel infrastructure, and;

- Fossil fuel risk trust funds capitalized by surcharges on all fossil fuel product transactions in a local economy and used to compensate public agencies, businesses, and individuals for more generalized risks of fossil fuel infrastructure in their regions such as earthquake swarms or groundwater pollution as well as the costs of climate disasters, climate adaptation and mitigation.

FOSSIL FUEL RISK BOND PROGRAMS ARE ROOTED IN EXISTING POLICY MECHANISMS

These mechanisms are not new ideas. Some degree of financial assurance is required for onshore and offshore oil and gas wells and hazardous waste. FFRB programs represent a logical extension of these to all classes of fossil fuel infrastructure and for the total economic value (TEV) of damages associated with worst-case scenarios. As envisioned, FFRB programs would also bar self-insurance or self-bonding as a mechanism given the fact that these forms of financial assurance are often lost in corporate ownership shuffles or bankruptcies that plague the fossil fuel industry.[2]

Surcharges to pay for infrastructure improvements are not new either – surcharges on water bills routinely pay for upgrades to wastewater infrastructure. FFRB programs would extend the concept to wholesale trade of fossil fuels to pay for adaptation and other climate costs incurred by public agencies. A number of states, counties, and municipalities have begun to identify financial needs for big ticket climate adaptation measures, and it is fairly straightforward to design a surcharge to capitalize a fossil fuel risk trust fund (FFRTF) to meet those needs at the time the investments are needed. Alternatively, if funds are needed sooner, FFRTFs can be capitalized by bonds at any time and paid back with the surcharge proceeds.

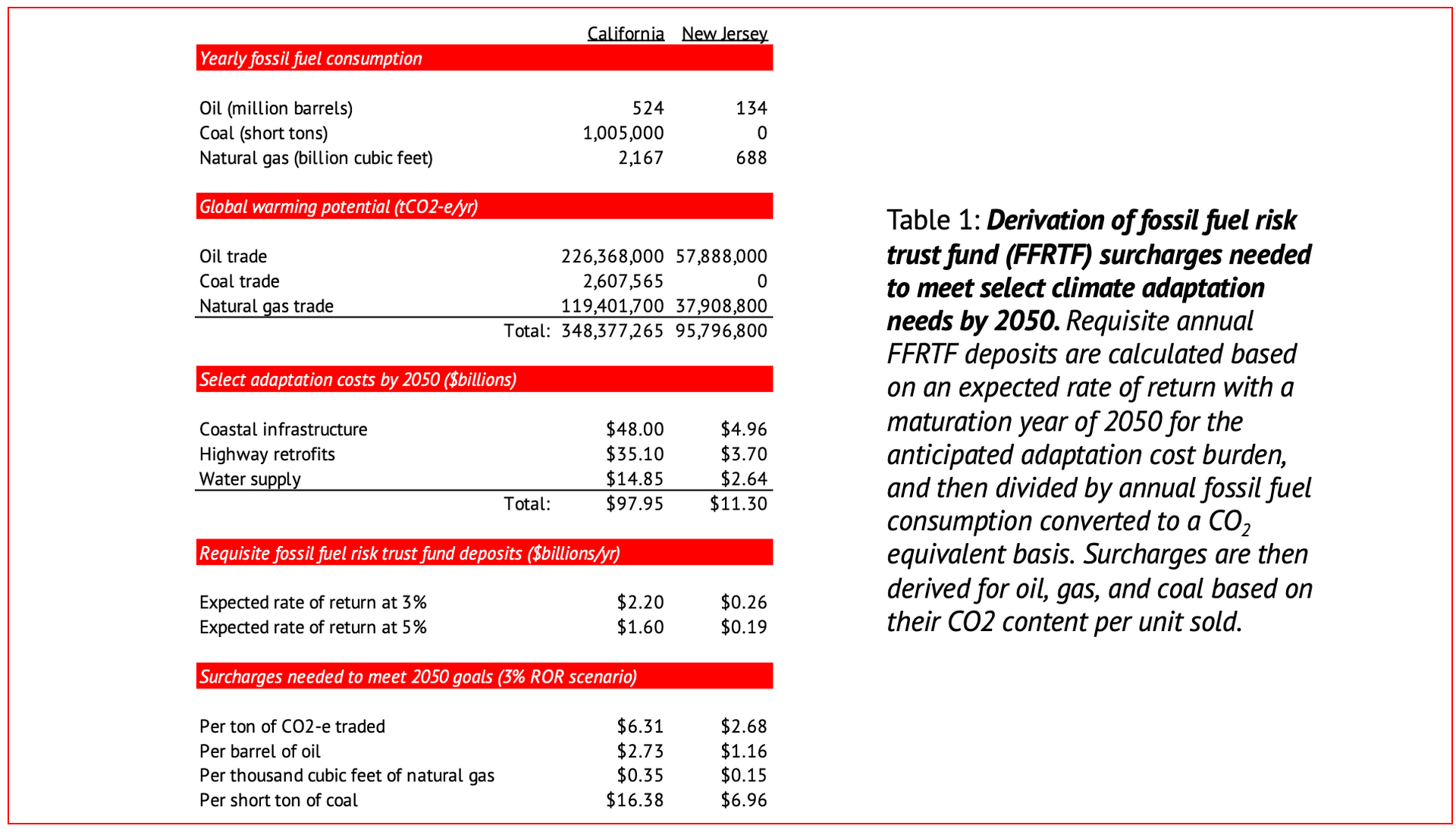

New Jersey and California provide an example (Table 1). In New Jersey, unmet climate adaptation needs to control coastal flooding, retrofit highways, and harden water infrastructure within the greater New York metropolitan region have been estimated at roughly $11.30 billion. [3] In California, adaptation needs within these same categories are projected to be nearly $98 billion. [4] Assuming these are inflation adjusted and needed no later than 2050 it is relatively straightforward to calculate the amount that needs to be deposited annually to ensure that those funds are available.

As with most other trust funds, FFRTF investments would primarily be invested in public debt securities with a relatively low rate of return. In our example, if the expectation is for a 3% annual return, then annual deposits in New Jersey would need to be in the order of $260 million. California would need deposits of roughly $2.2 billion per year. Dividing these figures by the quantity of fossil fuel trade in each state in CO2 equivalent terms results in a surcharge of $6.31/tCO2-e in California and $2.68/tCO2-e in New Jersey. Using standard emissions factors for various types of fossil fuels, this translates into surcharges per barrel of oil, thousand cubic feet of natural gas, and short ton of coal reported in Table 1. To prevent these surcharges from being passed on to consumers, legislation or ordinances adopted to levy such charges can be accompanied by language prohibiting such a pass on, although the legal authority to do so may be challenged.

UPDATE ON PACIFIC NORTHWEST INITIATIVES

While CSE is working at the national level and in six states with NGOs and elected officials to promote FFRB programs the most exciting developments come from the Pacific Northwest where three separate processes have been kicked off by the organizing work of CSE and its partners. Here, advocates have been promoting a model of FFRB implementation that unfolds in three distinct phases:

- Phase I – enabling legislation. While authority for implementing FFRB programs may already exist in a given jurisdiction, it is helpful to solidify that authority through enabling legislation. As recommended by CSE and its partners, that legislation should include findings connecting the dots between fossil fuel infrastructure and public health and safety risks and allocation of funds for an economic risk assessment to establish the legal basis for subsequent regulation.

- Phase II – risk assessment. Once commissioned, the risk assessment quantifies the anticipated public financial costs associated with worst-case accident and disaster scenarios for fossil fuel infrastructure as well as the anticipated costs of climate change, mitigation, and adaptation. A gap analysis looking at the adequacy of financial assurance and adaptation funding is also conducted during this phase as well as recommendations for policy interventions to close this gap.

- Phase III – program implementation. Through rulemaking or ordinance, a jurisdiction adopts new financial assurance requirements for fossil fuel facilities based on the gap analysis and a surcharge for fossil fuel transactions to offset anticipated public financial costs.

Three case studies demonstrate how FFRB initiatives are moving forward in this region. They include Multnomah County, Oregon, King County, Washington, and the State of Washington with respect to oil spill liabilities.

Multnomah County, OR – Portland’s Critical Energy Infrastructure Hub

In 2019 the Multnomah County Commission adopted a Phase I resolution opposing new fossil fuel infrastructure and initiating work on a FFRB program to “require the fossil fuel industry to bear the full cost of damages potentially caused by transporting and storing fossil fuels.” The resolution included findings that made a clear link between the storage, refining, transport, trade and combustion of fossil fuels and a wide range of local health, safety, environmental and economic risks. It is important to make these findings in order to ward off legal challenges based on federal or state preemption (i.e. Interstate Commerce Clause) and keep FFRB program initiatives firmly grounded in a local jurisdiction’s police powers.

The resolution initiated a Phase II analysis of economic risks associated with a worst-case scenario at the Critical Energy Infrastructure Hub (CEI) in Portland along the banks of the Willamette River as a first step towards internalizing those risks through various financial assurance mechanisms or requirements for risk mitigation. The CEI HUB contains 630 tanks of petroleum-based liquids distributed over 220 acres, and stores over 90% of Oregon’s liquid fuels.

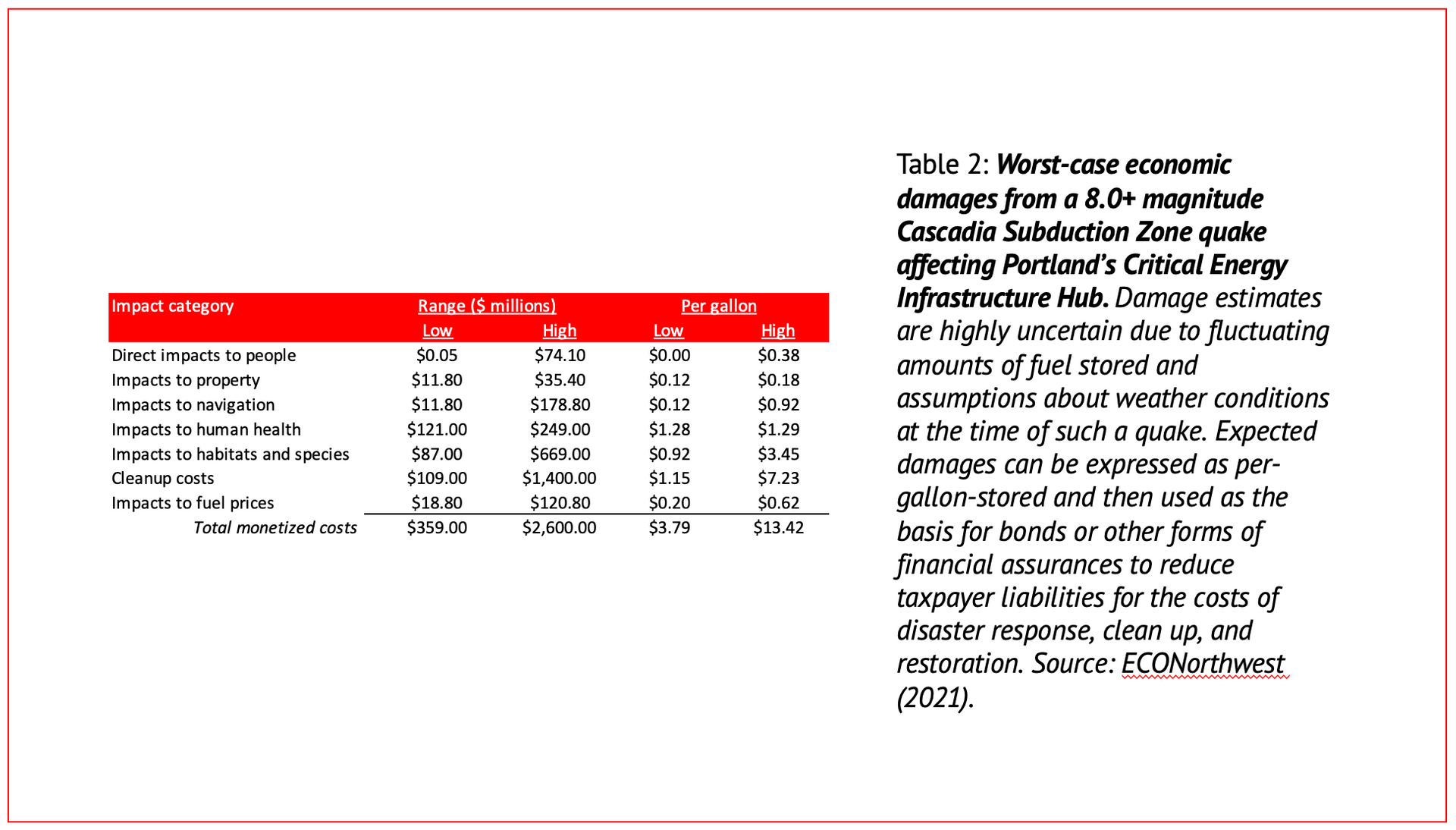

In early 2021, the Phase II risk analysis was completed by the firms ECONorthwest, Salus Resilience, and Enduring Econometrics.[5] The study found that in the event of magnitude 8 or 9 Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) quake – long overdue for the Pacific Northwest – a massive release of 95 – 194 million gallons of fuel would likely occur, some of which would catch fire and potentially result in a one or more catastrophic explosions. If at the high end, such a spill would be larger than the Deepwater Horizon disaster (~134 million gallons), making it the largest marine spill in US history. In terms of economic damages, the study considered a broad range of both market and non-market effects and assigned monetary values to seven (Table 2). Depending on the size of the spill, failure rate for storage tanks, and utilized capacity at the time of the quake, damages could range from a low of $359 million to a high of $2.6 billion.

With this tally of potential damage in hand, decision makers are now considering options for Phase III in order to shift these financial and economic risks back onto infrastructure owners. One scenario involves assessment of seismic related risks by individual companies (there are about 10 in the CEI), mitigation planning to harden this infrastructure, and (potentially) bonding against mitigation plans. Bonding for decommissioning is also on the table since in the event of a catastrophic quake, abandonment without post-catastrophe clean up and repair is a distinct possibility. In the spring of 2022, the Oregon Legislature passed SB 1567A to jumpstart this process. The state’s Department of Environmental Quality has begun a rulemaking initiative, and the initial round of facility assessments are expected to be completed by June 1st, 2024 as the legislature intended. After this, discussions over bonding against mitigation plans and decommissioning will begin in earnest.

An alternative, more direct pathway to Phase III regulations would require the Multnomah County Commission to enact financial assurance requirements and FFRTF surcharges on a track separate from the seismic risk assessments since SB 1567A does not explicitly call for either. As shown in Table 2, the basis for per gallon surcharges to offset potential public liabilities associated with a worst case CSZ quake exist now and so there is no real barriers to moving ahead with some form of a levy based on the ECONortwest et al. analysis. CSE and its partners will be pursuing this approach as we continue to monitor implementation of SB 1567A.

King County, WA – Final Phase III regulations now in place

In July of 2020, the King County Council enacted a Phase I ordinance in the form of amendments to its 2019 Comprehensive Plan establishing a new permitting system for fossil fuel facilities and a fossil fuel risk bond evaluation to lay the groundwork for new financial assurance requirements. As with Multnomah County, King County found that “the operation of fossil fuel facilities carries risk of explosion, leaks, spills and pollution of air and water,” which, in turn, subject nearby communities to a litany of health and safety risks. King County is an interesting case study for FFRB programs because there are no active permits or applications for fossil fuel facilities at this time in the unincorporated portions of the Seattle metropolitan area where the Council has jurisdiction. So enacting a FFRB program here is largely a deterrent strategy against new or expanded facilities.

King County’s Phase II risk assessment was completed in June of 2022. [6] The risk assessment concluded that three types of fossil fuel facilities could present public financial risks to the county in the form of costs related to health, safety, and infrastructure abandonment. These include thermal (gas) electric power plants, liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants and oil terminals. The assessment found sufficient evidence of past high-cost incidents to propose requiring proof of adequate financial coverage for explosions from any of the three types of facilities. It also recommended that self-bonding not be accepted as a financial assurance mechanism to cover financial risks associated with potential explosions or site contamination and that advance planning around potential onsite hazards and facility decommissioning be required along with financial assurances against these potential public liabilities.

A draft ordinance was subsequently prepared to enact these recommendations, and in May of 2023 the King County Council adopted a final Phase III ordinance putting these FFRB program recommendations in place. With this, King County has become the first US county to enact a full policy “trifecta” on the FFRB program concept. The Phase I, II, and III materials provide an excellent template to guide development of FFRB programs in jurisdictions across the US with or without significant concentrations of fossil fuel infrastructure.

State of Washington – New financial assurance rules for oil vessels and onshore facilities

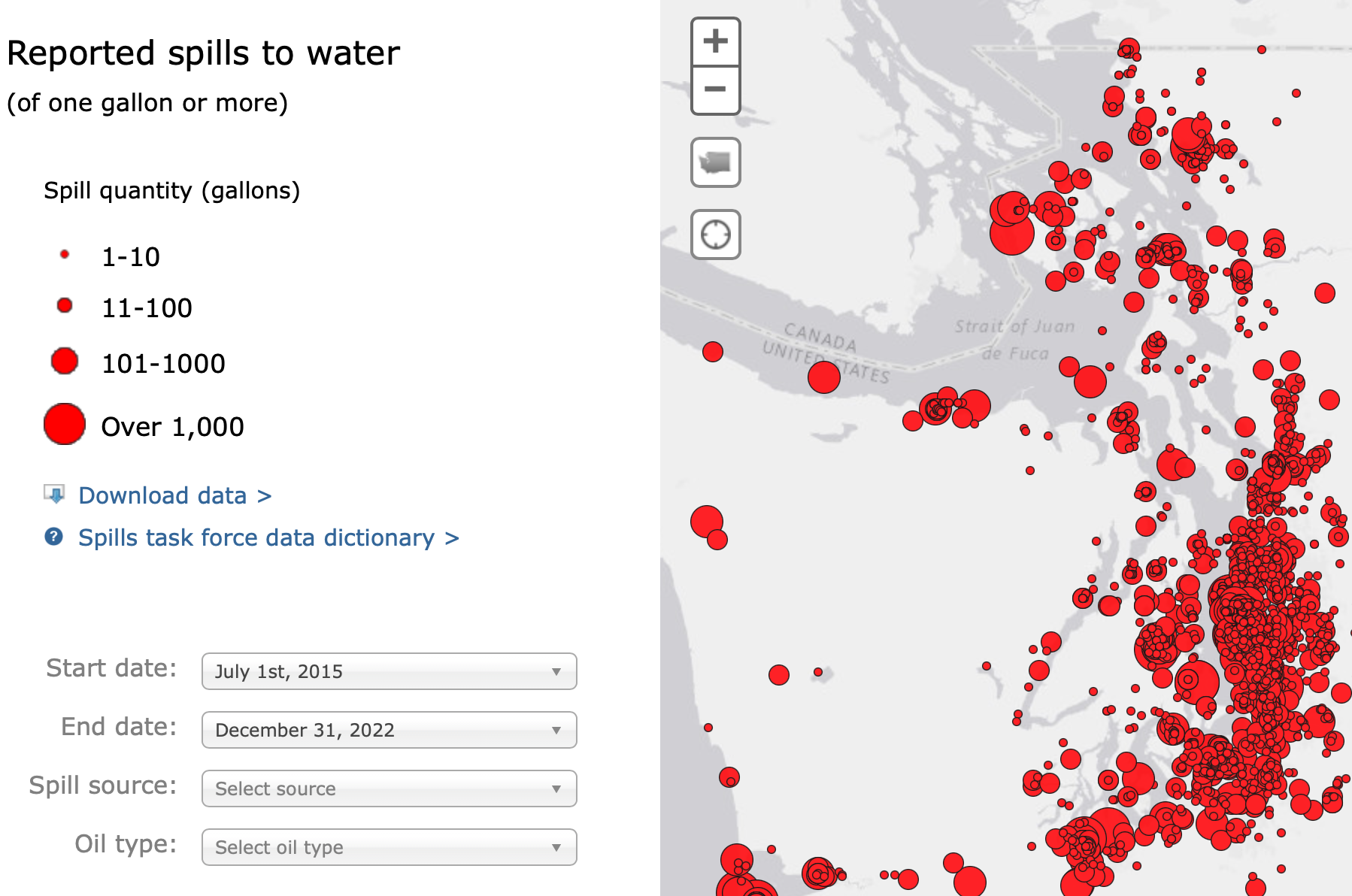

Led by Representative Mia Gregerson (D-33) the Washington legislature passed HB 1691 in the spring of 2022 as a first step towards implementing fossil fuel risk bond programs at the state level. HB 1691 requires the owners or operators of any covered oil vessel or oil facility to obtain a certificate of financial responsibility from the Department of Ecology (DOE) that guarantees such owners fully cover the costs of a worst-case spill. Acceptable forms of financial assurance include insurance, surety bonds, corporate guarantees, letters of credit, certificates of deposit, or protection and indemnity club membership. The legislation does not prohibit, but instead puts conditions on self-insurance as an option. Oil spills of all sizes are frequent visitors to Washington’s waters (Figure 1), and HB 1691 was seen as a way to start shifting the significant cost burden of monitoring and responding to these spills to fossil fuel infrastructure owners. For the largest oil tankers, financial assurances of at least $1 billion are now required.

Initially, Rep. Gregerson drafted a more comprehensive statewide Phase I bill that would have expanded Department of Ecology’s existing financial assurance requirements for hazardous facilities to include fossil fuel infrastructure. The first step in this statewide approach would have been a Phase II DOE report to the legislature evaluating the financial and economic costs and risks associated with fossil fuels and climate change, a gap analysis of existing financial assurance requirements, and recommendations to the legislature of how to close those gaps. DOE reviewed the legislative proposal and concluded that the analysis would cost about $1 million to complete – a price tag a bit too high to fly under the radar screen and avoid political pushback. Of course, investing $1 million to avoid potentially billions of dollars of economic costs is a great deal for public finance, but in a political climate of fiscal austerity such a price tag for the Phase II study was enough to derail the more comprehensive approach. As an alternative, HB 1691 is viewed as an incremental, but important step forward.

The law is a bit complex, and DOE is now charged with initiating a host of new rules to comply. These include (a) a rule governing the effective date for owners and operators of covered vessels or facilities to obtain the required certificates of financial responsibility; (b) a rule limiting use of a self-insurance option provided that such a rule must require the applicant to thoroughly demonstrate the security of the applicant’s financial position; (c) a rule governing the suspension, revocation, and re-issuance of certificates of financial responsibility; (d) a rule to evaluate whether an applicant for a financial responsibility certificate for an onshore or offshore facility has demonstrated an ability to compensate the state and other governmental entities for damages that might occur during a worst case oil spill, and, optionally (d) a rule to update the hazardous substances currently covered by the state’s existing financial responsibility requirements to maintain consistency with the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA).

CONCLUSIONS

Lord Stern famously stated that climate change is the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen.[7] As the foregoing demonstrates, fossil fuel risk bond (FFRB) programs provide states, counties, and cities an option for taking this market failure head on by shifting the public cost burden of both fossil fuel infrastructure and climate change back to where it belongs – on the polluters. By forcing fossil fuel infrastructure owners to internalize costs that are now passed on to taxpayers, FFRB programs have the potential to disincentivize applications for new or expanded facilities and relieve fiscally stressed governments from the ever-growing costs associated with climate disasters, climate adaptation, and mitigation of greenhouse gases.

The Pacific Northwest case studies illuminate both the promise and complexities of enacting FFRB programs at the state and local levels. In Multnomah County, Oregon, the key driver was the specter of a CEI Hub oil spill even larger than Deepwater Horizon and public financial costs that could top $2.6 billion. Given the urgency of avoiding such costs in the event of a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone quake, decision makers here opted for a Phase III process that accelerates adoption of seismic risk mitigation measures by individual companies rather than a program of financial assurances or a fossil fuel risk trust fund to offset a wider range of climate related costs.

In King County, Washington, the key driver was deterrence. The Pacific Northwest has been in the crosshairs of the fossil fuel industry – 50 large coal, oil or gas projects proposed since 2012 – and having a FFRB program in place is here provides an expensive regulatory hurdle that may prove too high to overcome. The absence of new applications for fossil fuel infrastructure permits allowed the full policy trifecta to be embraced and enacted without major opposition. At the state level in Washington, the cost of the Phase II risk assessment was deemed too high and forced legislators to revert to a less comprehensive approach focused on financial assurance requirements for oil vessels and onshore oil facilities. Despite the normal twists and turns of taking policy interventions from concept to on-the-ground reality, the PNW experience with FFRB programs should provide a workable model for other states, counties and cities across the US where fossil fuel infrastructure is now concentrated or where new applications are on the rise.

FOOTNOTES

[1]. Anil Markandya, Deger Saygin, Asami Miketa, Dolf Hielen and Nicholas Wagner. The True Cost of Fossil Fuels: Saving on the Externalities of Air Pollution and Climate Change. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency, 2010.

[2] Robert Schuwerk and Greg Rogers. It’s Closing Time: The Huge Bill to Abandon Oilfields Comes Early. New York: Carbon Tracker Initiative, 2020.

[3] Jesse M. Keenan. Regional Resilience Trust Funds: An Exploratory Analysis for the New York Metropolitan Region. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, Graduate School of Design, 2017.

[4] Leah Fischer and Sonya Ziaja (lead authors). California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. Sacramento, CA: Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, CA Energy Commission, CA Natural Resource Agency, 2018.

[5] EcoNorthwest, Salus Resilience, Enduring Econometrics. Impacts of Fuel Releases from the CEI Hub due to a Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake. Portland, OR: Multnomah County Office of Sustainability, 2022.

[6] King County Comprehensive Plan Workplan Action 20: Fossil Fuel Risk Bonds Report. Seattle, WA: King County Department of Local Services, 2022.

[7] Nicholas Stern. Stern Review on The Economics of Climate Change. London, HM Treasury, 2006.